Tim Rutherford-Johnson (the Rambler) has a post on music pandering to its audience, with a number of links to other blogs, including an article by critic Simon Reynolds casting similar glances at an Evan Parker concert back in the 1980s. Both posts discuss the cliquish aspects and in-jokes of musical "scenes" and the degree to which outsiders may be intimidated by these behaviors. Both are worth reading, including the links they reference, but I had a couple of other thoughts on the subject.

For starters, there is a tendency to ridicule the inner circle as fanboys, and to extend that ridicule to the artists that produce the music. But there's no accounting for taste, and it is very difficult to say why a particular music is "good" or "bad" (these are value judgments, not substantive critiques). And not every piece of music serves the same purpose. Years ago I heard an interview with Lester Bowie, the great trumpeter from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, where he said, "When I go to a party, I don't want to hear no Art Ensemble!" Tim mentions various cover bands as examples of fanboy music, but so what? When Roger Waters toured with a Pink Floyd cover band and played Dark Side of the Moon last year, was it fanboy music because they basically duplicated the classic, 35-year-old album note for note? All of the air guitarists in the audience (and I count myself among them) knew the solo in Money exactly, so we would have been sorely disappointed if the solo had been completely different. Maybe it was pandering, but it aspired for spectacle and entertainment, succeeding admirably on both counts.

Anyone who has spent a lot of time listening to music (or digging into any serious art form) will find that some work resonates, and some does not. The most interesting music writing attempts to explain why a piece of music succeeds when we take it on its own terms. It's a waste of space and time to say that a given piece of art sucks, because it merely reflects the author's value judgments, which are highly unlikely to match anyone else's. Music listeners are faced with an impossible amount of music to absorb, much less hear even once, so we have to choose carefully what albums or songs we listen to, what artists we support, what music we purchase. And every serious musician, sooner or later, will find an audience. For more obscure music, such as the kind I write about here, the audience is very small and scattered around the world, but it's there none the less. The Rambler's article centers on music with obscure references that only the cogniscenti will find, but what makes them a less valuable audience than the couple hundred people who buy boutique CDs from respected labels like Mystery Sea, Die Schachtel or 12k?

In addition, Reynolds finds himself attracted to John Butcher's oppositional stance as expressed in a recent Wire interview, and therefore more willing to revisit his music. But just because Butcher expresses a "bracingly stern stance" doesn't mean that I have to agree with it in order to like his music, any more than I need to be an anti-semite to like Wagner or Céline, or mentally ill to appreciate Van Gogh. Reading about an artist's motivations are interesting and may shed insight into the resulting music, but the artist's perspectives are just as unique as the listener's. I read a lot about John Cage, but the most interesting writing illustrates how his philosophy (which I find appealing because of my own personal history) manifests itself in his music, and not how his father's vocation as an inventor may have influenced his thought processes that led to the prepared piano.

We all have individual and completely unique personal histories which make up our tastes, and we make decisions every day that have as much to do with our personal aesthetics as anything remotely functional. Our clothes, the decorations in our homes, and the music that we listen to, all gives our lives an aesthetic meaning — and it doesn't matter if we are the only ones who understand all of our own references. If there is any pandering in music journalism, it's the glib turn of phrase that turns humiliation and ridicule into amusement. The appeal to our baser instincts is the least common denominator, analogous to the negative campaigning that too often passes for political discourse.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Oooh, he did it again!

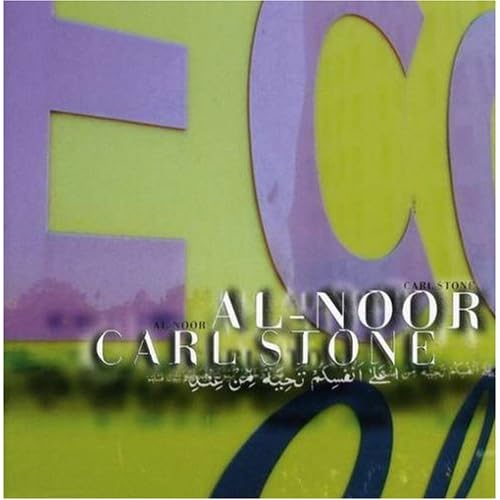

In a world where musicians become synonymous with a brand, making it easy and safe for consumers to acquire the newest version, no matter how slightly it differs from the previous ones, Carl Stone's recent album Al-Noor demonstrates that he has retained a capacity for surprise. His earlier releases cover a fairly wide swath of electonic music, but spend a lot of time on slow-moving static development. Nyala, his full-length minimal work for electronics and percussion released in 1996 on the renowned ambient label Em:t, is one of his most sought-after works and commands astronomical prices in the used CD market.

In a world where musicians become synonymous with a brand, making it easy and safe for consumers to acquire the newest version, no matter how slightly it differs from the previous ones, Carl Stone's recent album Al-Noor demonstrates that he has retained a capacity for surprise. His earlier releases cover a fairly wide swath of electonic music, but spend a lot of time on slow-moving static development. Nyala, his full-length minimal work for electronics and percussion released in 1996 on the renowned ambient label Em:t, is one of his most sought-after works and commands astronomical prices in the used CD market. With Al-Noor, Stone verges on plunderphonics territory mined by John Oswald because the majority of the album is clearly and unabashedly based on pop music. Apart from the title track, which is based on treatments of an extended loop of a solo female singer, nearly all of the pieces collected here have the steady, toe-tapping rhythm section that we all associate with pop. Not since the title track of his 1992 New Albion album Mom's (which to my mind always sounded like a twisted Talking Heads song) has Stone spent so much effort on pop structures. Jitlada is closest to Mom's, unrecognizable samples of a song, lyrics and hooks cut into unintelligibility, layered and looped back on themselves. Flint's (from a live recording) has a great beat and pre-articulate vocals that remain just beyond comprehension. Stone doubles the BPM rate after a few minutes, and the continuous percussive drive and faster speed increases the intensity, almost reminding me of the conclusion to Oswald's masterpiece Plexure. L'os à moelle (Bone marrow), the last work, is the longest on the album, a looping and deconstruction of a lite rock instrumental that Stone spins out for almost a half hour. Also based on a live recording (at the Apple store in Tokyo), it's a dazzling dismemberment and reconstruction of the song, extracting different instruments and circling them off in different directions.

The most befuddling piece on the album isn't on the CD at all, it's the internet-only bonus track, Dino's. First, it's the most obvious pop music ripoff of the five tracks, with the original lyrics clearly comprehensible, so that even somebody in the dark about recent pop phenomena can trace the song back to its origins as the smash hit of a pop diva turned tabloid fodder. Any commentary on this track simply begs to use high-minded critical theory terms like 'recontextualisation', or 'intertextuality' — my head hurts already. Then there's the placement of the track — it's not on the album, it's only available with the download version. Al-Noor's label has credits and notes at their web site, but since Dino's isn't on the CD, it's not mentioned specifically in the credits. And with so many news and commentaries about the death of the CD, and with many labels including bonus material with the physical media, it's still somewhat unusual for a label to encourage customers to purchase the download version rather than the physical one (although there are many rational reasons why they should do so).

Now I guess what Stone has done to the original hit single constitutes fair use, perhaps as a parody. But compared with parodists like Weird Al Yankovic, Stone's track doesn't seem very funny (at least you can tell that Weird Al is making a joke). The diva in question has done far more to parody herself than anything Stone can devise. So maybe we're left with the track on its own merits, but even though Stone's processing changes some of the harmonies and is attractive enough, knowing about the original track raises enough recontextualisation (oops, I did it again) questions to make this a head-scratcher.

This unsettling feeling is exactly why I keep coming back to Stone and follow his work from album to album. From displaced pop to drones, from sound sculpture manipulation to Tokyo field recordings, and through collaborations with Tetsu Inoue and email modification with Otomo Yoshihide, Stone continues to show the immense variety of what can be done with a laptop. I haven't been disappointed yet.

The download version of Al-Noor, including Dino's, is available from iTunes, Amazon, and emusic. The CD is available from the usual sources.

Monday, May 19, 2008

String ambient reviewed

The Webbed Hand string ambient collection that I mentioned a while back has gotten a mention in the music blog Disquiet, characterizing my track as 'hall-of-mirrors echoes which will surprise just about any listener.' My name is misspelled, but I've gotten used to that over the years. I even got certificates of achievement from various employers who made the same mistake. No matter, Cheers, and Thanks!

Thursday, May 15, 2008

A High Window

Lately I've been working on High Window, a recent piano work by the Japanese composer Jo Kondo. Kondo is somewhat more elusive composer than his predecessor Toru Takemitsu. Although his official biography says that he's written four books on his musical aesthetics, none of them has been translated into English, and I haven't found much else about him in English either. His music is poorly represented in recordings. The Swiss label hat[now]Art released two albums of his music about ten years ago, one of solo piano music and one of chamber music. Violinist and conductor Paul Zukovsky has also released a couple of albums, one of recent orchestral works coupled with an old recording by the Nexus percussion group, and one of an opera. But most of the albums listed at his publisher's discography are on Japanese labels and out of print. None of his music is available for legal downloads as far as I can determine.

Lately I've been working on High Window, a recent piano work by the Japanese composer Jo Kondo. Kondo is somewhat more elusive composer than his predecessor Toru Takemitsu. Although his official biography says that he's written four books on his musical aesthetics, none of them has been translated into English, and I haven't found much else about him in English either. His music is poorly represented in recordings. The Swiss label hat[now]Art released two albums of his music about ten years ago, one of solo piano music and one of chamber music. Violinist and conductor Paul Zukovsky has also released a couple of albums, one of recent orchestral works coupled with an old recording by the Nexus percussion group, and one of an opera. But most of the albums listed at his publisher's discography are on Japanese labels and out of print. None of his music is available for legal downloads as far as I can determine.Composer/blogger Daniel Wolf includes his early works among the landmarks of minimalism, but it's a very different minimalism than what is ordinarily found under that rubric (and he's not mentioned in any of the books I have on musical minimalism). In an interview posted at his publisher's site, Kondo addresses the perception of minimalism in his compositions. He prefers to consider his music as the art of being ambiguous, which is another perspective on a music that reduces itself to a few bare essentials. It's just that the essentials that Kondo keeps are different from the ones chosen by Glass, Riley, and the other, more famous minimalists.

Nevertheless, I agree with the minimal assessment, especially with the piano piece entitled High Window. Written in 1996 for pianist Satoko Inoue (who has recorded it twice), High Window is a chorale, a series of softly played chords that, as Kondo wrote in the liner notes for the Hat piano album, "exemplify my own procedures concerning chordal formations and their progressions,... the type of 'harmony' best suited to my personal style." Typically chorales have some kind of melody, so one of the challenges of this piece is to decide whether a melody exists, and, if so, where it might be located. It's not as simple as a Bach chorale, which has four voices throughout, voices that can be traced from one chord to the next, and which sometimes depart from the chordal structure to create a separate entity. Kondo's chords typically have between six and nine notes each, almost all tightly packed into a two-octave span. Traditional tonal voice leading seems irrelevant, although the opening chord recurs eleven times at various points in the piece, including five times in the first minute and four times at the end, including the penultimate position, thus providing a point of stability.

He has a couple of techniques to vary the texture. Although all of the chords during the first minute or so have the same duration, about four seconds, enough time for the quiet sound to decay significantly, almost to silence. In the middle of the piece, he alters the pace by shortening the chords to varying degrees. Three times during the piece, he specifies that the pedal should be held for a two or three chords. One time only, he places the same chord twice in succession (and holds the pedal for these two chords). Four times he slows the tempo briefly and creates a more complex sound; these sections have the lowest notes in the piece and use the pedal to hold all of the notes until the end of the section. Three times, he prolongs a chord after a moment with a quiet minor ninth interval. And for the final minute, he adds the same single high note, like a tiny bell, after every chord.

So what am I to make of this piece? I think the title provides a clue, although this is pure speculation on my part and has no bearing whatsoever in any text by Kondo that I can find. A high window lets in light, but apart from a glimpse of sky and clouds, you can't see out of it. From our perspective below the window, we have to look up, at the ceiling, which is usually painted white, and, apart from some fixtures, is undecorated. Passing people and cars outside the window change the light with their reflections, perhaps sending an occasional bright flash across the ceiling. Otherwise, the light changes slowly, with the hours and with the seasons. Like the reflections in the high window, each chord in the piece exists only for itself. I hear no melody connecting one chord to the next. It's like a slideshow of close textured material, such as tree bark, pine needles or sand, where each picture is just slightly different from the ones before and after.

I've considered how the piece would be different if it had been written for strings, or some set of instruments with more sustain than the piano (and in fact, some of his orchestral works use similar techniques). But the slideshow effect would be completely missing with a more continuous sustained sound, and while each chord has a limpid sound hanging by itself, the sequence brings about a sense of wonder and uncertainty in a music as static as any drone piece one might imagine.

I took the photograph of the library at Biosphere 2, which is at the top of a small tower. I didn't have any photos of the kind of high window I imagined for Kondo's piece, so this one will have to do.

Update: During a coaching session with Kondo at SICPP 2008, his interpretation differed considerably from mine. I've put his comments here.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

In the rainbow

Those who pay attention to corporate pop distribution have already noticed that the back catalog of the Rolling Stones was available earlier this year for one month only on emusic before disappearing back into the higher margin catalogs like iTunes and Amazon. But today, I see that the (in)famous recent Radiohead album, In Rainbows, is available on emusic. Digital Audio Insider follows these stories closely, so check him out if you want more details (including some interesting speculation on why the Stones catalog disappeared). Glad I waited…

Thursday, May 8, 2008

Roots of interpretation

Jean-Jacques Nattiez's book Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (available from Powells or Amazon) hypothesizes a musical work as a series of configurations, from composition to listening, in one of the most stimulating works I've read in some time. It explicitly acknowledges a problem with music analysis that I have always felt intuitively, which is that very often the explanations that we get for new music don't seem very relevant toward understanding. How many times have I read that such-and-such a piece is based on a specific tone row? Am I supposed to hear the row as a 'theme' in the way that Beethoven uses the technique? Not likely. Am I supposed to hear inversions (retrograde and otherwise), or uses of the row in chords? Not very likely either. One thinks of the detailed documentation that Lev Koblyakov made of the compositional processes involved in Pierre Boulez' work Le marteau sans maître, which are not required to appreciate the beauty of the piece.

Instead of considering that an account of the compositional processes explains a piece of music, Nattiez distinguishes three distinct areas of concern in music analysis, what he calls the tripartite analysis: the process by which the music is composed, the musical work itself (which Nattiez identifies with the score because a realization of the score is already a kind of interpretation or analysis), and the process by which the music is perceived. Of course, being French, he must cultivate his jargon and create new words for the compositional and perceptual processes, but this is the cost of new ways of understanding. And my oversimplified explanation should not eclipse the nuances and subtleties that Nattiez evinces in his descriptions of the musical work.

One of the most fruitful suggestions from the separation of concerns for Nattiez' tripartite analysis is that multiple analyses are possible for a specific situation, and Nattiez spends some time in the final chapter covering some of the many analyses of Wagner's Tristan chord. Although Nattiez refuses to go to a complete relativism that would allow any possible explanation, he seeks to place an analysis in a larger schema that he calls a 'plot', a pre-established set of criteria that an analyst will use for guidance. Musicians perform the same operation. When I play Takemitsu's piano pieces, I have in mind the whole story that I have constructed in my mind for Takemitsu's place in music, and which I've outlined in previous posts. When I read Burt on Takemitsu, I may gain understanding about the compositional processes, but it is the perceptions that I have about Takemitsu that are more important. I don't hear the scale that he may have used in a particular composition, I hear the poetic effects and the colors.

Nattiez leaves out one very important process in musical understanding, which is the work a musician does in order to turn the musical score into an audible artifact. Traditional analysis doesn't necessarily translate into better performances, but often seems directed at creating better composers. A performer must not only make decisions about the meaning and intent of a musical work, but must be able to translate those decisions into sound. This is a different kind of work altogether from a scholarly analysis. Nattiez also glides fairly quickly over contemporary electronic works that exist only as recordings, saying that it 'would be easy enough to identify and describe the sound-objects that make up these works' — as a reviewer of various electronic works, let me respectfully disagree. An impartial description of an electronic recording is extraordinarily difficult if not impossible to make, and the examples that Nattiez adduces (such as the listening score for Ligeti's Artikulation) were all made with significant assistance and cooperation from the composer.

While I was reading Music and Discourse, the John Cage mailing list had a discussion about Atlas Eclipticalis, a work I've written about before. Various correspondents testified to a significant oral tradition around Cage's music that remains essentially undocumented. Daniel Wolf paraphrased composer Richard Winslow: "if you want to reproduce something precisely, transmit it orally; if you want to guarantee that something changes over time, write it down." While I somewhat reluctantly agree with Petr Kotik's assertion that all notated music must be learned by direct encounter (after all, I still take piano lessons), Cage's scores are tantalizing entry points to a unique perspective on sound and music. And frankly, it's not easy to find a teacher with a direct lineage back to Cage, in the way that my previous teacher traced her Bach lineage to Rosalyn Tureck. The ambiguity inherent in a Cage score is part of the attraction, and I feel compelled to deal with his music, and that of his successors, because even when I get it wrong, the effort still moves me closer to understanding and enlightenment. Nattiez illustrates some of the problems inherent in interpreting a score, the decisions a musician must make to realize music from the score, all while examining the assumptions that provide the unstated background for this sublime and mysterious activity.

Instead of considering that an account of the compositional processes explains a piece of music, Nattiez distinguishes three distinct areas of concern in music analysis, what he calls the tripartite analysis: the process by which the music is composed, the musical work itself (which Nattiez identifies with the score because a realization of the score is already a kind of interpretation or analysis), and the process by which the music is perceived. Of course, being French, he must cultivate his jargon and create new words for the compositional and perceptual processes, but this is the cost of new ways of understanding. And my oversimplified explanation should not eclipse the nuances and subtleties that Nattiez evinces in his descriptions of the musical work.

One of the most fruitful suggestions from the separation of concerns for Nattiez' tripartite analysis is that multiple analyses are possible for a specific situation, and Nattiez spends some time in the final chapter covering some of the many analyses of Wagner's Tristan chord. Although Nattiez refuses to go to a complete relativism that would allow any possible explanation, he seeks to place an analysis in a larger schema that he calls a 'plot', a pre-established set of criteria that an analyst will use for guidance. Musicians perform the same operation. When I play Takemitsu's piano pieces, I have in mind the whole story that I have constructed in my mind for Takemitsu's place in music, and which I've outlined in previous posts. When I read Burt on Takemitsu, I may gain understanding about the compositional processes, but it is the perceptions that I have about Takemitsu that are more important. I don't hear the scale that he may have used in a particular composition, I hear the poetic effects and the colors.

Nattiez leaves out one very important process in musical understanding, which is the work a musician does in order to turn the musical score into an audible artifact. Traditional analysis doesn't necessarily translate into better performances, but often seems directed at creating better composers. A performer must not only make decisions about the meaning and intent of a musical work, but must be able to translate those decisions into sound. This is a different kind of work altogether from a scholarly analysis. Nattiez also glides fairly quickly over contemporary electronic works that exist only as recordings, saying that it 'would be easy enough to identify and describe the sound-objects that make up these works' — as a reviewer of various electronic works, let me respectfully disagree. An impartial description of an electronic recording is extraordinarily difficult if not impossible to make, and the examples that Nattiez adduces (such as the listening score for Ligeti's Artikulation) were all made with significant assistance and cooperation from the composer.

While I was reading Music and Discourse, the John Cage mailing list had a discussion about Atlas Eclipticalis, a work I've written about before. Various correspondents testified to a significant oral tradition around Cage's music that remains essentially undocumented. Daniel Wolf paraphrased composer Richard Winslow: "if you want to reproduce something precisely, transmit it orally; if you want to guarantee that something changes over time, write it down." While I somewhat reluctantly agree with Petr Kotik's assertion that all notated music must be learned by direct encounter (after all, I still take piano lessons), Cage's scores are tantalizing entry points to a unique perspective on sound and music. And frankly, it's not easy to find a teacher with a direct lineage back to Cage, in the way that my previous teacher traced her Bach lineage to Rosalyn Tureck. The ambiguity inherent in a Cage score is part of the attraction, and I feel compelled to deal with his music, and that of his successors, because even when I get it wrong, the effort still moves me closer to understanding and enlightenment. Nattiez illustrates some of the problems inherent in interpreting a score, the decisions a musician must make to realize music from the score, all while examining the assumptions that provide the unstated background for this sublime and mysterious activity.

While we're waiting for a post with some substance....

A meme, from my friend Brian.

1) Pick up the nearest book.

2) Open to page 123.

3) Find the fifth sentence.

4) Post the next three sentences.

5) Tag three people, and acknowledge who tagged you.

At the moment, the only book on my desk is uncracked, so I have literally no idea of what will come of this.

And more still: even in this "moment," the musical-ness of music will often be due to an even briefer conjunction, the briefest instant within a brief moment, an opportune minute, one beat of a single measure — like the ravishing chord in Chabrier's Sulamite, like the captivating harmonic sequence in Chaikovsky's Dumka, or the Gregorian cadence at the end of Fauré's fifth piano prelude. The Charm hangs on the imponderable musical-ness of a brief occasion, a lightning strike of an event.

But can one install wisdom on the seat of this delicate, imperceptible point in an ephemeral instant?

-- Vladimir Jankélévitch, Music and the Ineffable

Wow. Can't wait to read the lead-in. Tag to music bloggers DaveX and Marcus and literary blogger Maitresse (who must have some interesting books sitting around, since she just passed her orals — in Paris, no less).

1) Pick up the nearest book.

2) Open to page 123.

3) Find the fifth sentence.

4) Post the next three sentences.

5) Tag three people, and acknowledge who tagged you.

At the moment, the only book on my desk is uncracked, so I have literally no idea of what will come of this.

And more still: even in this "moment," the musical-ness of music will often be due to an even briefer conjunction, the briefest instant within a brief moment, an opportune minute, one beat of a single measure — like the ravishing chord in Chabrier's Sulamite, like the captivating harmonic sequence in Chaikovsky's Dumka, or the Gregorian cadence at the end of Fauré's fifth piano prelude. The Charm hangs on the imponderable musical-ness of a brief occasion, a lightning strike of an event.

But can one install wisdom on the seat of this delicate, imperceptible point in an ephemeral instant?

-- Vladimir Jankélévitch, Music and the Ineffable

Wow. Can't wait to read the lead-in. Tag to music bloggers DaveX and Marcus and literary blogger Maitresse (who must have some interesting books sitting around, since she just passed her orals — in Paris, no less).

And posts with some substance are in preparation.

Saturday, May 3, 2008

String ambient compilation

Back from vacation with a brief announcement: the netlabel Webbed Hand Records has released a two-disk compilation of ambient music based on stringed instruments. I composed Cathedral, a twenty-minute drone work, almost entirely from piano sounds a few years ago (there is a little bit of field recordings buried in the mix), so I submitted an excerpt from this piece for the compilation. There are 22 pieces in total, covering a pretty wide spectrum of styles, and I am pleased and honored to be included in this compilation.

Back from vacation with a brief announcement: the netlabel Webbed Hand Records has released a two-disk compilation of ambient music based on stringed instruments. I composed Cathedral, a twenty-minute drone work, almost entirely from piano sounds a few years ago (there is a little bit of field recordings buried in the mix), so I submitted an excerpt from this piece for the compilation. There are 22 pieces in total, covering a pretty wide spectrum of styles, and I am pleased and honored to be included in this compilation. Webbed Hand is one of the better netlabels I've found, with a number of interesting releases. I especially recommend their Rain series, which contains a number of long-form tracks inspired by rain sounds. Like their inspiration, the Rain pieces are sometimes soothing, sometimes more intense, but all freely available, and all worth checking out.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)